What is a Cleft?

Cleft lip (cheiloschisis) and cleft palate (palatoschisis), which can also occur together as cleft lip and palate, are variations of a type of clefting congenital deformity caused by abnormal facial development during gestation. A cleft is a fissure or opening—a gap. It is the non-fusion of the body's natural structures that form before birth. The face of a child begins to develop at approximately seven to nine weeks after conception. The lip develops first at about seven weeks and the roof of the mouth, which is the hard and soft palate, at about the ninth week. As the lip and the palate develop independently, it is possible to have either a cleft of the lip, a cleft of the palate or a combination of both.

Cleft Lip

If the cleft does not affect the palate structure of the mouth it is referred to as cleft lip. Cleft lip is formed in the top of the lip as either a small gap or an indentation in the lip (partial or incomplete cleft) or it continues into the nose (complete cleft). It is due to the failure of fusion of the maxillary and medial nasal processes (formation of the primary palate). The alveolar ridge (the portion of the bone where the teeth grow through the gum) may also be cleft. The lip can be cleft to any degree on one side (unilateral) or on both sides (bilateral).

Cleft Palate

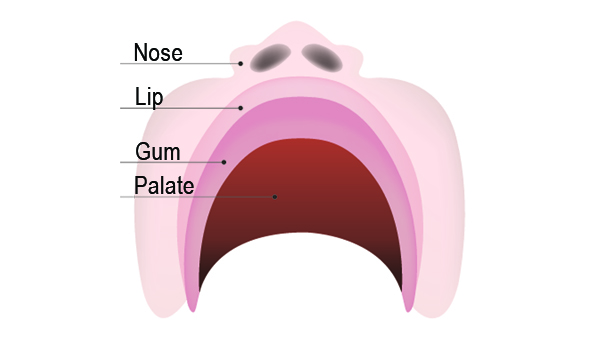

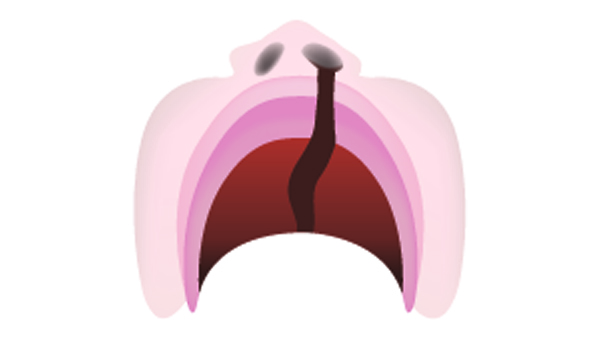

Cleft palate is a condition in which the two plates of the skull that form the hard palate (roof of the mouth) are not completely joined. Palate cleft can occur as complete (soft and hard palate, possibly including a gap in the jaw) or incomplete (a 'hole' in the roof of the mouth, usually as a cleft soft palate). When cleft palate occurs, the uvula is usually split. It occurs due to the failure of fusion of the lateral palatine processes, the nasal septum, and/or the median palatine processes (formation of the secondary palate).

The hole in the roof of the mouth caused by a cleft connects the mouth directly to the nasal cavity.

Note: the next images show the roof of the mouth. The top shows the nose, the lips are colored pink. For clarity the images depict a toothless infant.

Pierre Robin Sequence

Some cleft babies have Pierre Robin Sequence which is characterised by an unusually small mandible (micrognathia), [1] posterior displacement or retraction of the tongue (glossoptosis), and upper airway obstruction. Incomplete closure of the roof of the mouth (cleft palate), is present in the majority of patients, and is commonly U-shaped.

cause

The development of the face is coordinated by complex morphogenetic events and rapid proliferative expansion, and is thus highly susceptible to environmental and genetic factors, rationalising the high incidence of facial malformations. During the first six to eight weeks of pregnancy, the shape of the embryo's head is formed. Five primitive tissue lobes grow:

- a) one from the top of the head down towards the future upper lip; (Frontonasal Prominence)

- b-c) two from the cheeks, which meet the first lobe to form the upper lip; (Maxillar Prominence)

- d-e) and just below, two additional lobes grow from each side, which form the chin and lower lip; (Mandibular Prominence)

If these tissues fail to meet, a gap appears where the tissues should have joined (fused). This may happen in any single joining site, or simultaneously in several or all of them. The resulting birth defect reflects the locations and severity of individual fusion failures (e.g., from a small lip or palate fissure up to a completely malformed face).

The upper lip is formed earlier than the palate, from the first three lobes named a to c above. Formation of the palate is the last step in joining the five embryonic facial lobes, and involves the back portions of the lobes b and c. These back portions are called palatal shelves, which grow towards each other until they fuse in the middle. This process is very vulnerable to multiple toxic substances, environmental pollutants, and nutritional imbalance. The biologic mechanisms of mutual recognition of the two cabinets, and the way they are glued together, are quite complex and obscure despite intensive scientific research.

genetics

Genetic factors contributing to cleft lip and cleft palate formation have been identified for some syndromic cases, but knowledge about genetic factors that contribute to the more common isolated cases of cleft lip/palate is still patchy.

Many clefts run in families, even though in some cases there does not seem to be an identifiable syndrome present, possibly because of the current incomplete genetic understanding of midfacial development.

Environmental influences may also cause, or interact with genetics to produce, orofacial clefting. An example for how environmental factors might be linked to genetics comes from research on mutations in the gene PHF8 that cause cleft lip/palate (see above). It was found that PHF8 encodes for a histone lysine demethylase and is involved in epigenetic regulation. The catalytic activity of PHF8 depends on molecular oxygen a fact considered important with respect to reports on increased incidence of cleft lip/palate in mice that have been exposed to hypoxia early during pregnancy. In humans, fetal cleft lip and other congenital abnormalities have also been linked to maternal hypoxia, as caused by e.g. maternal smoking, maternal alcohol abuse or some forms of maternal hypertension treatment. Other environmental factors that have been studied include: seasonal causes (such as pesticide exposure); maternal diet and vitamin intake; retinoids - which are members of the vitamin A family; anticonvulsant drugs; alcohol; cigarette use; nitrate compounds; organic solvents; parental exposure to lead; and illegal drugs (cocaine, crack cocaine, heroin, etc.).

What causes a cleft?

There is no single cause of cleft lip and/or palate. Research tells us it’s often caused by a combination of different genetic and environmental factors, but because of the huge number of factors involved it can be very difficult to narrow these down.

Genetics is all about things inherited from family members, like eye and hair colour. Sometimes there is a clear family link, other times it just happens as a ‘one off’.

Environmental factors mean things that happen just before or during pregnancy, like taking a certain medicine or how the baby starts growing in the womb.

Most of the time, a cleft is caused by genetic and environmental factors coming together in a way which can’t be predicted or prevented.

If you have a child with a cleft, it is very unlikely to be because of something you did or did not do.

Around 15% of clefts are caused by syndromes, where one or more symptoms occur all together. If a syndrome is involved, the chances of passing on a cleft is all down to the heritability of the syndrome, which in some cases can be as high as 50%.

An isolated cleft palate (where the lip is not affected) is believed to have a different cause to cleft lip and palate. So a family affected by cleft palate (but not cleft lip) may only be likely to pass on cleft palate.

There are a huge number of factors that affect how likely someone is to have a cleft, including race, sex, and many different environmental factors that are almost impossible to predict without a careful look at an individual’s genetic history and circumstances.

environmental factors

There have been a number of environmental factors linked to a higher chance of a baby developing a cleft. These include well-known risks in pregnancy such as smoking and heavy alcohol consumption, as well as less obvious factors like taking certain prescription medications.

It is important to note that these are just factors, and that the causes of cleft are usually much more complicated than what someone did or didn’t do while pregnant. Even the healthiest, well-planned pregnancies can result in a cleft, and this is no one’s fault.

To find out more about what caused your/your child’s cleft, see if your Cleft Team can arrange genetic testing (see below).

genetic factors

While some conditions can point to a single genetic factor as a cause, there have been a number of different genes identified as increasing the risk of having a child with a cleft.

It may also be a matter of certain environmental factors switching genes on or off as a baby is developing in the womb. This is called ‘epigenetics’.

genetic testing

Genetic testing (also called genetic counseling or evaluation) aims to work out how likely you are to pass on a trait such as cleft lip and/or palate. Parents may want to know how likely they are to have another child with a cleft, and adults with a cleft may want to know how likely they are to pass their cleft on to any future children.

It usually involves several steps, including putting together a detailed family history, medical history, a physical examination of the person affected and even laboratory testing. It all depends on the individual and what they’re looking for. The most important part of this for people with a cleft is confirming that the cleft is isolated and not part of a syndrome, as this will change how likely it is to happen again. The type and severity of a cleft also has to be considered, and this might be harder if there are different types in one family.

At the end of this session or series of sessions, the geneticist and/or genetic counselor will tell you what they’ve found and if they think any further treatment is needed (in cases of a syndrome), and they will also be able to tell you how likely it is that you will pass on a cleft to any children.

Related conditions and syndromes

Sometimes a cleft is caused by part of a ‘syndrome’, which is when lots of different symptoms happen together. One of these symptoms can be a cleft lip, a cleft palate, or a cleft lip and palate.

There are over 400 conditions and syndromes that list a cleft as a symptom. Some of these syndromes and conditions are very rare and usually occur as a ‘one off’, others have a 50% chance of being passed on.

Estimates can vary widely, but based on UK statistics, only around 15% of clefts happen as part of a syndrome or condition.

What are the chances of having a child with a cleft?

Some conditions like Sickle Cell Anaemia are relatively easy to predict – we know which gene causes it, and we can work out the chances of a child inheriting the condition or being a carrier based on whether or not their parents are carriers. The causes of cleft lip and palate are much more complicated and vary greatly from case to case, so even if both parents have a cleft it can be very difficult to accurately predict how, if at all, their children will be affected. Each case needs to be looked at separately.

The below statistics are based on multiple studies looking at a range of different populations, however they are only observations, not predictions, and are subject to change depending on the available evidence. If you want to know more about your particular case, you should talk to your Cleft Team about genetic testing or evaluation.

1/700 people will be born with a cleft lip and/or palate, though some statistics put it is closer to 1/600.

This is around 0.14% of the population. A cleft is the most common craniofacial (to do with the skull or face) abnormality in the world, and in the UK alone three babies will be born with a cleft every day.

In general, the more people who have a cleft in a family, and the closer they’re related to a child, the more likely that child is to have a cleft. However, it should be noted that some studies put the number of ‘random’ cases without any recurrence in a family as high as 50-75% amongst certain populations, so it’s extremely hard to predict without detailed genetic analysis.

Parents with a cleft

If there is one parent with a cleft, the chances of a child having a cleft is between 2-8%. If a parent is affected as well as their own parent, sibling or existing child, the chances of future children having a cleft is around 10-20%. It is important to remember that a cleft may be caused by another condition or syndrome which has not been diagnosed, in which case the chances of inheriting the cleft will be very different.

Siblings and other relatives with a cleft

While having a lone affected uncle, aunt, cousin or another more distant relative does increase the chances of having a child with a cleft, it’s estimated to be by less than 1%. Siblings of a person with a cleft only have around a 1% chance of passing this on. This goes up to 5-6% chance if they have other affected close family members.

Unaffected parents

Where there is no family history and the cleft was not caused by a syndrome or condition, the chances of having a child with a cleft is around 0.14%, or 1/700. If neither parent has a cleft, but they have one child with a cleft, the chance of another child also having a cleft is 2-8%, and this goes up the more children with a cleft they have. If someone else in the family (such as an uncle or aunt) also has a cleft, this goes up to 10-12%.